It isn’t only about federal aid:

Fighting stigma surrounding food insecurity in immigrant communities

According to Boston Indicators, food insecurity rates doubled in Massachusetts from 8 percent to 16 percent between 2019 and 2020. Nationwide, this was a period of uncertainty due to the massive unemployment and the lack of conditions to provide food and other necessities. During this time, many people heavily relied on federal aid programs, and emergency food organizations such as community kitchens, food banks, and food pantries, creating a sense of urgency, evidenced by the pandemic affecting these communities and food access.With an economic panoramic in shambles, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, but undocumented immigrants did not receive this aid. As a result, despite comprising 20 percent of the Massachusetts essential workers labor force in 2018 and around 25 percent by the quarantine of 2020, they were one of the most affected demographics in Massachusetts.“Trying to aid immigrant communities is exhausting, not because they do not cooperate but because the federal money and sources are directed to only half of the population, those lucky enough to be citizens or legal residents.” —Enessa Skopljak

According to Skopljak, the Chelsea Community Garden Groundskeeper and Salvation Army Chelsea Corps Community Center volunteer leader, shared that aiding immigrants in Chelsea, MA, and East Boston, MA felt overwhelming due to the absence of government funds foreordained to helping undocumented immigrants.“In the Chelsea garden and with the Salvation Army Center, the most we could do to help people during and after quarantine was providing safe food as much as possible and as often as we could. Besides that, we could not do much since our resources depended on the City, the Federal government, or donations.”

The pandemic was a scenario that exposed the food insecurity risk for immigrant communities in short and long-term eventualities due to the absence of federal assistance. Unfortunately, CARES is not the only federal assistance program for which undocumented immigrants are not eligible; a long-term program such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is also inaccessible to undocumented immigrants.Levels of food insecurity and SNAP federal aid accessibility

The complexity of federal aid accessibility feels like a labyrinth for many foreign-born populations at risk of food insecurity. For those who, as Enessa said, “are lucky enough to be citizens or legal residents,” the challenges are still ascending to access SNAP. Rosario, an immigrant single mother, says that despite having two native-born children, she opted to seek aid in her community soup kitchen rather than requesting her children’s rightful federal benefits.“When I was pregnant with my second child, the doctor told me about food stamps, but I did not understand what it was for, and when I asked my coworkers — most of them undocumented like me — they said that they preferred not to get involved in the government’s system because one might get deported and I did not ask anything else about it. It was scary to think about me being deported when my two children were born in this country.”

After a couple of years, Rosario could be guided by a pre-K teacher at her daughter’s school. The teacher explained that she would not be deported or involved in any lawfulness if she applied for SNAP, that it was just a myth meant to keep the stigma and immigrants limited from this type of resources. For Rosario, it was an opportunity to support her children as a low-income single mother.However, when she tried to fill out the applications, the language was highly elaborate and having the Spanish versions did not help her current situation. Filling the long and extenuating formularies and collecting documentation she did not know where to get was as frustrating as thinking she could be deported for sharing this information.This is not unexpected; in the supplemental SNAP report of nutrition assistance programs households of 2020, USDA documented that only 5.1 percent of the U.S. naturalized foreign-born population and only 9.8 percent of Massachusetts’s naturalized foreign-born population participate in SNAP.Rosario is not the only case; she represents many immigrants who have been misinformed or not appropriately guided. There are cases like Rosario’s, whose children are eligible for SNAP, or others who are directly suitable for this aid and do not request it out of frustration due to the language and the bureaucratic steps. Or fear of someone under their care or them being deported, losing their children, or having any legal consequences.Gina Plato-Nino, SNAP Deputy Director at Food Research and Action Center, addressed this issue, she said:“Technical language is a skillset…a lot of the language that is utilized within the staff applications are very technical language. So it does require professional interpretation and sometimes that’s not necessarily given but there are ongoing conversations with the Department of Transitional Assistance to figure out how to, how to address this, and how to make it a priority.”

The DTA has conceivable support for Massachusetts residents who have difficulty applying for or maintaining their SNAP benefits. DTA has a collaborative effort between local government agencies and community organizations to assist people through SNAP outreach units. The SNAP outreach unit can collaborate with people, their local Transitional Assistance office, and community organizations to assist participants in getting and keeping SNAP benefits.In the state of Massachusetts, 100 SNAP outreach partners work with DTA, with just over 20 of them working in the Greater Boston area:The Outreach partners can assist people in completing the SNAP application, interim report, and recertification, understanding the application process, gathering and submitting required proofs, and remaining SNAP eligible by assisting with the recertification process.Intersecting struggles: Food insecurity, income, poverty, and migratory status

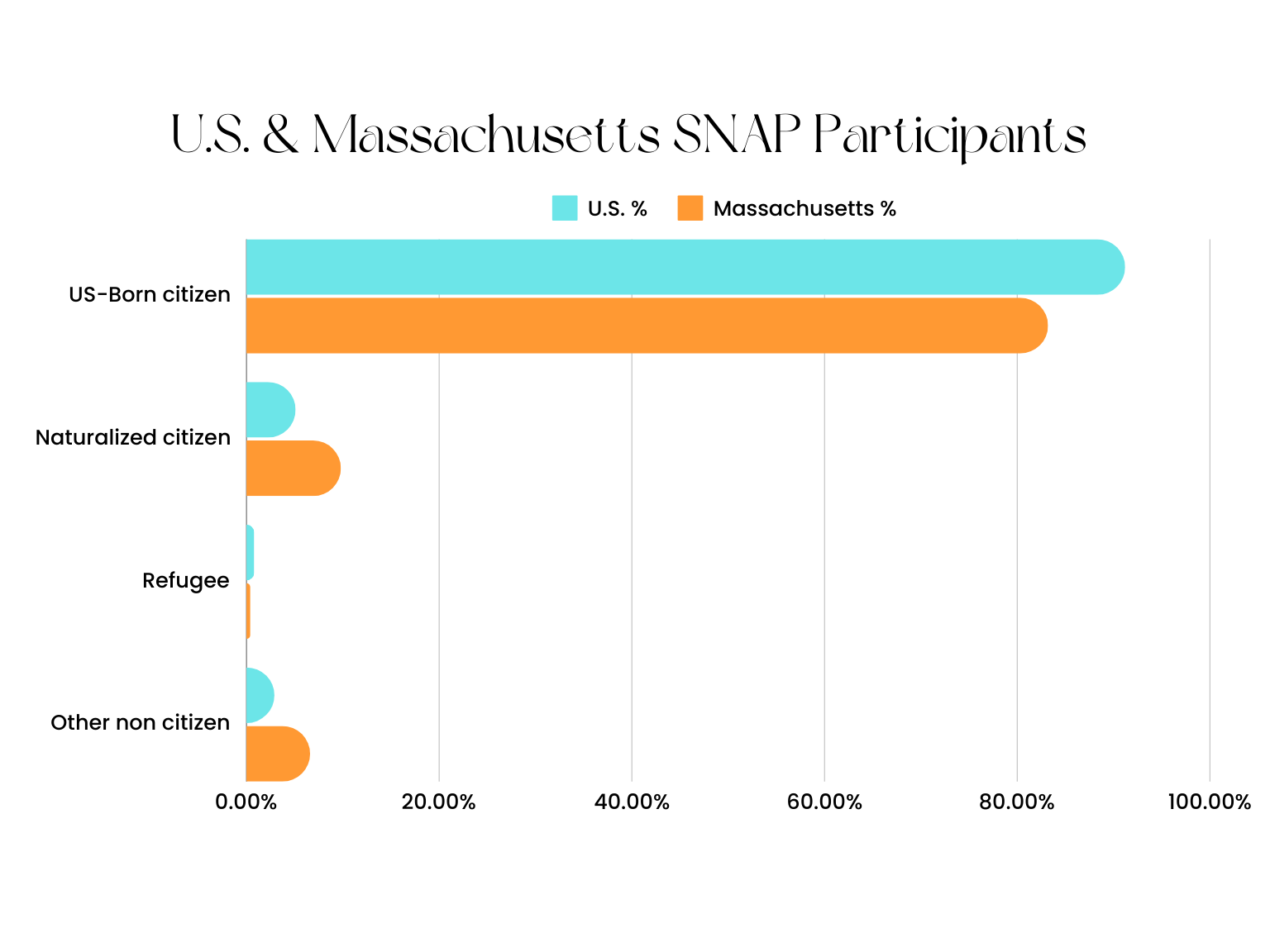

Between 2020 and 2021, the foreign-born demographic constituted 13 to 14 percent of the U.S. population, and 7 to 8 percent were non-citizens, in brief words, undocumented immigrants. In addition, 12 percent of the total foreign-born population lives below the poverty rate. Also, immigrants earn only 30 percent of the total U.S. average income in the same period.This pictures the intersectional struggles of immigrant communities; food insecurity, poverty, and low income. Also, there should be awareness that poverty and low income are significant triggers of food insecurity — intertwined struggles that can be simultaneously solved.According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), only U.S. citizens and certain lawfully present non-citizens are eligible for SNAP benefits, usually only available in extreme migratory circumstances (refugees, victims of trafficking, and Asylees under particular circumstances). In addition, non-citizens who qualify for SNAP based on their immigration status must also meet income and resource limits.In 2002 the Farm Bill (P.L. 107–171) restored eligibility for SNAP to “qualified” immigrant adults who have been in the U.S. for at least five years. The bill also restored eligibility to immigrants receiving certain disability payments and eliminated any waiting period for refugees, asylees, and “qualified” immigrant children under age 18. Moreover, the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113–79) required states to use an immigration status verification system and an income and eligibility verification system for SNAP.Less than 9% of SNAP participants were born outside the United States — 5% were naturalized citizens, 1% were refugees, and 3% were other non-citizens (lawful permanent residents and other eligible non-citizens). In the pre-pandemic period, 7% of all SNAP participants were citizen children living with non-citizen adults.7.5 to 8 percent of the foreign-born population are non-citizens and undocumented immigrants who are not eligible for federal aid programs. This means that 5 out of 10 immigrants do not have access to SNAP, a long-term relief. But looking at data nationwide felt unreasonable, but taking a closer look could have improved the panoramic, but it did not.In Boston, MA, 28.2 percent of the population is constituted by immigrants, which by demographic seems to be a no too underserved community when we look at the SNAP Outreach Partner distribution locations map in Boston, provided to assist and make accessible this resource. Yet, out of the total foreign-born population in Boston, 14.1 percent are undocumented, making half of the immigrant population underserved and ineligible for SNAP.• • •

This was critical during the pandemic picks, especially during quarantine, since the low income and poverty levels pushed immigrant communities dependable on emergency food organizations and federal aid. Undocumented immigrants, mainly, had limited options to access food assistance and other social safety-net programs because of their immigration status.

Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance 2020 report on Social assistance applications, primarily for SNAP. Visualizations by Sara Valentina Alvarez Echavarria.

Share of population 18+ who themselves or their households access free food and where they get it, Massachusetts, 2020. Visualizations by Sara Valentina Alvarez Echavarria.

Arline Olivero Perez, Operation Coordinator and Director Assistant of East Boston Community Soup Kitchen, expressed that their non-profit organization can be a temporary relief. Still, they do not count on financial assistance to cover the impact of SNAP or other federal aid programs.“When we receive immigrants, most of the time we provide them with food pantry as we do for the rest of the community and we help them with our limited non-profit sources. Then we introduce them to other resources that might cover their necessities; if they need to go to a shelter we will guide them to where they are supposed to be going or to who they are supposed to be talking.”

The East Boston Community Soup Kitchen is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, also described as a charitable organization that serves as public support and safety organization. They carry out their exempt purposes by supporting other exempt organizations, usually other public charities.“Because we are a non-profit 501 ©(3) organization, we do not require people to provide any proof of residency or migratory status. Everyone is welcome to walk in and tell us their situation and we will take care of it. For us, it doesn’t matter their gender, race, migration status, or any information they do not feel comfortable sharing. The only information we handle is their current situation so we can provide as much as possible.”

Amid uncertainty and lack of resources, it is an undocumented-friendly temporary relief for immigrants. Still, it is provisional, and aid scarcity for non-naturalized immigrants is the inequity elephant in the room. Arline expresses that even after the pandemic economic deterioration, it is still intricating to support undocumented immigrants who go through hardship. As a result, multiple non-profit organizations, including food pantries, school programs, religious charity organizations, and other community support systems, have come together to collaborate.“There are a lot of new immigrants and immigrant families coming into East Boston specifically so from week to week we have been seeing an increase in the number of people that we receive in the community soup kitchen. Mainly after this new immigration wave, we have been partnering with other organizations and programs like us,” says Arline.

The pandemic showcased a sense of urgency for diverse demographics of the United States, but this insecurity has been part of the daily lives of immigrant communities for generations. So now, what needs to be done if we know how food insecurity influences poverty and income — and vice versa?Debunking myths & what needs to be done?

According to the Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), to fill that gap in SNAP eligibility, states can create and fund food assistance programs that mirror SNAP and can take other actions to connect eligible immigrants and their families to SNAP as well as additional nutrition and food programs.Many foreign-born populations limit themselves from accessing SNAP due to Clinton’s 1996 farm bill. The 1996 Farm Bill (P.L. 104–127) and the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA, also known as Welfare Reform) (P.L. 104–193): Most non-citizens were made ineligible for SNAP. Efforts are being made inside Congress to eliminate the five-year eligibility requirement, such as the LIFT the BAR Act proposed in 2021. However, one year after the proposal, this bill is still under review through various subcommittees that oversee immigration, nutrition, and financial services.But what Gina Nino-Plato and FRAC’s Food over Fear Report recommends is education about federal aid and these communities. The fear of becoming a public charge, or penalized for seeking SNAP benefits, is entirely untrue. Recently the Biden administration codified rules that now, seeking SNAP, Medicaid, or housing benefits will not get non-citizens labeled as a public charge, effective December 23. The Food over Fear Report, created before this amendment, explains even eligible non-citizens are less likely to apply for benefits because they fear getting charged. It is a fear spread by disinformation that only gets resolved with a system-wide push for more precise information about the rule. Efforts have been made; Federal Nutrition Service, Under Secretary Stacy Dean, at the beginning of 2022, recommended outreach from SNAP agencies to local immigrant communities to remedy this problem.Community outreach from outside the government can also go a long way. For example, food insecurity among immigrant families is critical to their nutrition, health, well-being, and nation. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is an evidence-based program to do just that. Yet, SNAP remains unavailable to some immigrants. Outreach groups from pantries, restaurants, schools, hospitals, shelters and other care centers can build valuable relationships with communities afraid or unable to access federal support and know best what specific communities need.Finally, as some of the data should show here, there is no basis for non-citizens “stealing” benefits or for a significant portion of them to rely on welfare. Unfortunately, the rhetoric was echoed by former President Donald Trump throughout his presidency, pushing more fear and bigotry toward all immigrant communities. But through local and systemic education, this fear can be reduced, and the struggles of communities across Boston, Massachusetts, and the United States can be alleviated.Petra Wolf and Sara Valentina Alvarez Echavarria conducted and developed this research.

Our methodology:

Methodology of the Project ‘Fighting Stigma Surrounding Food Insecurity and Immigrant Communities’